i thought it might be a good idea to have a thread dedicated to local history were people can write posts not just about historical facts but also posts about local myths and legends concerning liverpool football club, the city of liverpool and the merseyside area in general.

it may help new fans or fans from around the world learn something about the history and culture of this great city that lies on the eastern banks of the river mersey and the football club that bears it`s name.

Do you know your history?

10 posts

• Page 1 of 1

You Can Shoot All The Blue Jays You Want To But Its A Sin To Kill A Mocking Bird

-

yckatbjywtbiastkamb - LFC Super Member

- Posts: 1435

- Joined: Fri Mar 26, 2004 8:19 pm

Hi mate,

there is a nice thread that Bermenstein started regarding facts and figures for the history of the club right here

http://www.liverpoolfc-newkit.co.uk/viewtopic.php?t=28401

there is a nice thread that Bermenstein started regarding facts and figures for the history of the club right here

http://www.liverpoolfc-newkit.co.uk/viewtopic.php?t=28401

-

metalhead - >> LFC Elite Member <<

- Posts: 17476

- Joined: Tue Oct 04, 2005 6:15 pm

- Location: Milan, Italy

David Kennedy

1

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

By David Kennedy

People ‘dressed’ their houses to advertise Cup Final footballing

allegiances, though my Mum would never allow my brother’s Evertonian

blue to go up in case neighbours or passers-by mistakenly took us for

Catholics – John Williams (football sociologist)1

It was strange in the 1930s for a Catholic to support Liverpool – John

Woods (Liverpool author).2

In Liverpool, even in the two-ups and two-downs, most Protestants were

Conservative and most Catholics were Labour, just as Everton was the

Catholic team and Liverpool the Proddy-Dog one – Cilla Black (singer)3

Being a Roman Catholic school, religion played a large part in our school

life. Pop Moran even tried to turn me off football at Anfield – Catholics

were traditionally Everton supporters and players, Liverpool were the

Protestant team. Pop honestly thought that being a Catholic I wouldn’t be

happy at Anfield – Tommy Smith (ex Liverpool FC player and captain)4

A sectarian division between Everton and Liverpool football clubs is, for some, an

irrefutable part of local football culture. There is a prodigious amount of

anecdotal evidence claiming Everton to be the team traditionally supported by

the city’s Catholic population and Liverpool being predominantly supported by

Protestants. For others, however, sectarian affiliation is more urban myth than

reality: a tribal impulse amongst some fans to shore up and sharpen their

identity by suggesting a deeper meaning to support for the two clubs.5 Orthodox

opinion lies with the latter viewpoint, and football historians in particular have

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

2

dismissed notions of sectarianism as being without foundation and a divisive

intrusion into the study of both clubs. The issue, though, has never been

investigated in any great depth and, perhaps, deserves closer scrutiny than the

cursory attention afforded it. Whilst the claim of religious differences has little or

no meaning in defining the relationship of the modern day Everton and Liverpool

football clubs, the specific question to address is whether there is any justification

for the perception that, in an earlier period, the basis for such claims existed?

§

Naturally, claims of past sectarian connections have been resisted strongly by the

clubs themselves. Official club literature goes to some lengths to deny this

possibility by stressing Everton and Liverpool’s shared origins in order to

downplay what they view as nonsensical claims of sectarian affiliation. However,

it would be a mistake to dismiss perceptions that each club has acted as standardbearer

for distinct communities simply because of their shared point of origin.

The split of Everton FC in 1892 that brought Liverpool FC into existence saw the

emergence onto the football scene of a body of men with strong political

identities. The men who controlled the fortunes of Everton and Liverpool football

clubs also took an active part in local politics and it would be strange, given the

political environment these men operated within, that football in the City of

Liverpool could have remained untouched from matters of religious controversy

and discretely contained in a purely sporting context. To understand why this

would be so it is necessary to take a short detour into the sectarian history of

Liverpool politics.

During the pioneering period of professional football in Liverpool, religious

sectarianism dominated local life – affecting housing, schooling, and the city’s

occupational structure. By the mid-nineteenth century almost a quarter of the

city’s population were Irish born, and by the century’s end Liverpool remained a

key destination point for an exodus of Irish Protestants and Catholics. Friction

between the city’s Protestant and Catholic populations was a feature of the social

landscape – on many occasions erupting into street violence and rioting between

David Kennedy

3

ethnically divided communities. Some historians have argued that the ferocity of

the hostility between Irish Catholics in Liverpool and the “native” British and Irish

Protestant community surpassed the sectarian divide in Scotland, and only stands

close comparison with the experience of towns of Northern Ireland: ‘Liverpool –

sister of Belfast, rough, big hearted, Protestant and Unionist’.6 Like no other

mainland British city, Liverpool reflected the contours of the ongoing struggle in

nineteenth century and early twentieth century Ireland between Unionism and

Nationalism over the matter of Home Rule for Ireland.

Liverpool, therefore, was a harsh environment for the class-based politics found

elsewhere in England to prosper in. The local Labour Party struggled to gain a

commanding foothold in the city until well into the twentieth century. ‘Liverpool’,

the frustrated Labour leader, Ramsey MacDonald, wrote in 1910, ‘is rotten and we

better recognise it’.7 The local Home Rule supporting Liberal Party and, more

especially, the Conservative-Unionist Party were more adept at competing for

civic power by recourse to ethno-religious politics. The Liberals used their

commitment to Irish Home Rule to appeal directly to many Irish voters. By forging

an alliance with the local Irish party, the Liberal agenda tended to be

synonymous in most people’s eyes with defending the rights of Catholic voters in

the city. Their political rivals predictably put the matter more bluntly. Tory

leader William.B. Forwood offered the stark choice to the municipal electorate of

being either:

…well governed by the Conservative Party as it had for the past 50 years,

or governed by Home Rulers who had no interest whatever in Liverpool

but were simply in the city council to further the political interests of

Home Rule in Ireland. It was not a question of handing over the control of

the council to Messrs Holt, Bowring and Rathbone [Liberal Party

grandees] but to Messrs Lynskey, Taggart and Kelly [Irish Nationalist

councilors].8

Liberal organisation, though, was weak in Liverpool compared to the

Conservatives, who rather more successfully courted the native working class

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

4

electorate by being “sound on the Protestant ticket”. As the party viewed by

many as the political representation of the ties between Church and state, the

Tories enjoyed a fruitful relationship with the Protestant majority amongst the

electorate. Liverpool’s Tory Party hierarchy had traditionally played on the

emotions of the Protestant working class of the city by appealing beyond their

class interests to their religious identity. A brand of popular Toryism, therefore,

carried the day in Liverpool: deference shown to the Tory elite by the Protestant

working class (and their support at the ballot box) was rewarded by the party’s

close identification with the values and institutions they held in esteem, and

opposition to any significant improvement in the condition of the Irish Catholic

working class – more especially in the fiercely competitive casual labour market.

By playing the Orange card in this way the Tories (for all but a handful of years in

the 1890s) retained municipal control of Liverpool until the 1950s.

The important point to make here is that, whereas in other towns the issues

primarily to be addressed and contested by local parties would be the more

prosaic matters of, say, housing and health provision, or the setting of rates, in

Liverpool “Imperial affairs” (that is, the stance taken by ward candidates on

religion and the Irish Question), were paramount. For this reason it would be

completely understandable, given the high incidence of football club directors

active in the local Liberal and Conservative parties, if ethno-religious labels

became attached to Everton and Liverpool football clubs via the politic views

held by those directors.

I have highlighted elsewhere the strongly partisan political dimension to the

Everton split in 1892: http://www.evertoncollection.org.uk/article?id=ART74553

In the wake of that event the Everton boardroom became a relative stronghold of

men involved in Liberal politics, whereas the Liverpool boardroom was an almost

exclusive preserve of men involved in some way with the local Conservative

Party. In the Everton boardroom, James Clement Baxter was Liberal city

councillor for Liverpool’s St.Anne’s ward; George Mahon – Everton’s first

David Kennedy

5

chairman – was committee member of Walton Liberal Association; Dr William

Whitford was chairman of Everton and Kirkdale Liberal Association; William.R.

Clayton was the chairman of Formby Liberal Association; Alfred Gates was

leader of the Liberal Party in Liverpool City Council. Two other Everton directors,

Will Cuff and Alfred Wade, were also involved in local Liberal politics.9 All seven

men would become chairmen of the club. By contrast, at Liverpool FC boardroom

involvement in local party politics was of a distinctly Conservative nature. Six

directors: Benjamin E.Bailey, Edwin Berry, John Houlding, William Houlding,

Simon Jude, and John McKenna were members of the Constitutional Association,

the ruling body of Liverpool Conservatism.10 The Constitutional Association

exercised complete control over district Conservative Associations in Liverpool

and affiliated societies and organizations such as the Orange Order. In the

council chamber John Houlding, Edwin Berry, William Houlding (John Houlding’s

son, and fellow director) and club secretary, Simon Jude, were Conservative

councilors representing neighbouring north Liverpool wards. Other Liverpool FC

directors involved in Conservative politics were: Harry Oldfield Cooper, a

member of the Liverpool Junior Conservative Club, and Thomas Croft Howarth,

the leader of the Conservative group in the Liverpool Parliamentary Debating

Society.11

It seems hard to believe that such stark difference in political complexion – and

the connotations they held – would escape the attention of a general population

keenly tuned-in to the attitudes of those involved in public life on matters of

religion. In fact, there were many public statements made by prominent club

members concerning the issues of religion, ethnicity and the all-pervasive matter

of Irish Home Rule to drive the differences home. For example, Everton director,

William Whitford, described as ‘an ardent Home-Ruler’, made an impassioned

speech during the municipal election campaign of 1892 against the blocking of

Home Rule by Ulster Unionists:

Ulstermen do not desire to govern Ireland according to the wishes of the

people of Ireland, but according to the narrow prejudices of the so-called

“loyal minority”. Irish Catholic bishops and priests had not the illegitimate

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

6

power we in this country are asked to believe. Their views are, however,

in accordance with the nationalist aspirations of the Irish people. The

priests had been loyal to the people, unlike the priests of other

denominations…The Irish priests could not and had not the power to lead

the Irish people in temporal matters against their honest convictions 12

Everton director and fellow Liberal-Nationalist, Alderman Alfred Gates (a name

which was ‘as a red rag to a furious bull’ to the Conservative-Unionist Party) was a

‘strenuous advocate of Home Rule’ keen to show that ‘the Orange Tory Party were

losing ground in Liverpool’. Another director of the club and Everton’s first

chairman, Dublin educated George Mahon, helped reorganise the Walton

Liberal Association in the wake of the defection of Liberal Unionists opposed to

Gladstone’s proposed solution to the Irish Question. Mahon was a prime mover in

the Walton Liberal Party’s adoption of the policy plank of Home Rule and was one

of the officers of that district body affirming in the local press their 'total support

for Home Rule'.13 And frequent press reports of directors James Clement Baxter

and Alfred Wade attending Irish Nationalist League meetings would have

underlined for the public a sense of the general sectarian tone of the men

inhabiting the Everton boardroom.14

From figures amongst the Liverpool FC hierarchy, on the other hand, there was

an equally strident and public outpouring of feeling toward the Protestant-

Unionist cause. Founder and Chairman of Liverpool FC, John Houlding, quite

obviously found it difficult to contain his religious leanings as a Conservative-

Unionist and Orangeman whilst carrying out his duties as a Guardian at the West

Derby Poor Law Union. As reported by the Liverpool Courier, as Guardian of the

West Derby Union Houlding pointedly refused granting to Catholic priests any

payment for ministering to Catholic inmates of workhouses whilst allowing such

payment to Church of England and Nonconformist ministers. In reply to a motion

put before the Poor Law Union to make the payment to Catholic priests ‘as an act

of justice and common fairness’ Houlding replied:

I defy any member of the Board or any judge in the land to show him an

Act of Parliament which expressly stated that they should pay Roman

David Kennedy

7

Catholics for services performed in workhouses. If English Unions did

appoint a Roman Catholic priest it is only done by a clear evasion of the

law, and often perhaps for the sake of quietness 15

Another Liverpool FC director, and a successor to Houlding as chairman, Edwin

Berry, leaves us evidence of his vigilance against the re-emergence of an

influential Roman Catholic Church in British society – a matter of much debate in

Liverpool political circles in the late Victorian period. Addressing an audience of

the British Protestant Union in 1898, Berry offered his support to ‘the repression of

lawlessness and Romanising influence’, declaring himself to be a ‘loyal

Churchman with every desire to further the principles of the Church of England

in accordance with the Reformation’. This was a position on the issue he

reiterated six years later when attempting to outflank the challenge of an

independent Orange Order candidate for his council seat.16

A close associate of both Houlding and Berry both in local political circles and at

Liverpool FC was MP for Everton and President of the National Protestant Union,

Sir James A Willox. Willox, the proprietor of the Liverpool Courier, was not a club

director but was an influential large shareholder in Liverpool FC, using a “proxy”

on the board to advance his interests in the club. Willox publicly backed the

decision to set up Liverpool FC out of the remnants of the staff left behind at

Anfield in the wake of the 1892 split and remained a close ally of the club’s board

until his death in 1905. A firebrand in the defence of British dominion over

Ireland, Willox, speaking to a meeting in his Parliamentary Division, attacked

Liberal policy on Ireland: ‘To conciliate four million people in Ireland’ he asked

his audience, ‘are we going to sacrifice one million and a half of loyal Protestants

and faithful lieges of the Queen?’. Speaking to another Conservative audience,

Willox called for ‘more of Cromwell’s courage and more of his religion’ in public

life. 17

The Unionist sentiments of the hierarchy of Liverpool FC are firmly underlined by

the connections many of their directors had with the Liverpool Working Men’s

Conservative Association (WMCA), an organisation affiliated to the Liverpool

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

8

Tory Party machine. The overlap of personnel between the Liverpool boardroom

and the WMCA gives us further scope in understanding how perceptions of a

sectarian football division between Everton and Liverpool could have taken root.

Described as ‘the engine of Protestant power’18 within Liverpool Conservatism,

the WMCA were at the vanguard of anti-Catholic politics in the city. To gain an

appreciation of the nature of this organization we can turn to the words of Barbara

Whittingham-Jones, a local political journalist writing at the height of the WMCA’s

power in the Inter War period. The WMCA and the Orange Order, declared

Whittingham-Jones, were as ‘identical in political outlook as in personnel’. She

described the proceedings on her visit to one branch meeting in 1936:

Meetings at Conservative clubs cannot proceed until an incantation has

first been declared by all present. The chairman opens the meeting by

requiring members who have been guilty of ‘consorting’ with Catholics to

confess their delinquencies and upon doing so they then receive a

warning. Catholics who have strayed in by chance are requested to leave

the room. Even Questions have to be preceded by the formula: “By my

Protestant faith and Conservative principles…” with hand raised in the

Hitler salute. Such is the democratic character of this sectarian classridden

caucus that no Roman Catholic workingmen can join the

Conservative Party in Liverpool or frequent the Workingmen’s

Conservative Association clubs.19

An organization ‘held together by its tough Orange fibre’, the Liverpool WMCA

was predictably staunch on the Irish Question, offering its support for the

maintenance of the Union with Ireland. The Association’s policy prior to the

partition of Ireland was to oppose the breaking up of the Union and to back the

reprisals carried out by the British auxiliary force, the notoriously brutal Black

and Tans, against Irish Republicans. Writing in 1920, the Liverpool WMCA

Chairman, Sir Archibald Salvidge, saluted Black and Tan operations as the

actions of ‘...those who will not submit meekly to the fiendish destruction of life

and property which Sinn Fein gunmen claim as noble acts of heroism…[but,

rather] give Sinn Feiners a taste of their own medicine’. In the aftermath of the

setting up of the Irish Free State in 1921, the Liverpool organisation’s emphasis

David Kennedy

9

merely switched to the safeguarding of Protestant Ulster and the adoption (no

doubt with one eye on local affairs) of “No Surrender” Unionist politics.20

The amount of people involved in the ownership and control of Liverpool FC in

the period under review who were also key figures in the WMCA is quite

remarkable. These included such club luminaries as John Houlding, Edwin Berry

and Benjamin Bailey – all chairmen of Liverpool at some point prior to the First

World War, and key players in this quasi-religious organisation. But the link was

a longstanding affair at the club, stretching beyond the First World War to the

1950s. Director, Albert Edward Berry, succeeded his brother Edwin as WMCA

solicitor in 1925, holding the position until 1931. This post was then passed on to

yet another Liverpool FC director and Conservative councillor, Ralph Knowles

Milne, a position he held until his death in 1954. The club’s solicitor in the 1940s,

Maxwell Fyffe, also provided a connection between Liverpool and the WMCA.

And at shareholder level too the connection was significant: John Holland, one of

the small number of shareholders involved in the club when it was formed in

1892, and who remained a shareholder until his death in 1914, was one of the

founding members of the Liverpool WMCA in 1867 and was the Association’s

longstanding secretary; the aforementioned Sir James A.Willox, was Vice

President of the WMCA. Conservative councillor, Ephraim P. Walker, a major

shareholder in Liverpool from 1899, was a member of the WMCA’s governing

council. And yet another significant shareholding connection was that of Bents

Brewery. Bents held shares in Liverpool FC at a time when control of the brewery

was in the hands of Archibald Salvidge, Chairman of the WMCA and Edward

J.Chevalier, Vice Chairman of the organisation.21

In the context of deep sectarian tensions in Liverpool society, the strong

connection the Liverpool board had with this avowedly sectarian organization is a

significant one. In this respect it is interesting to note that the Glasgow Working

Mens’ Conservative Association were equally central to the early development of

Glasgow Rangers FC.22 The reputation of the Glasgow club as a bulwark of

Protestant and Unionist ascendancy in the West of Scotland is well established.

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

10

The undoubted influence of the Liverpool WMCA on Liverpool FC’s development

perhaps demonstrates an unconsidered connection, therefore, between the

Merseyside club and that of the stridently Unionist Rangers.

And it is difficult to ignore another similarity in the boardroom profile of the

Liverpool and Glasgow clubs: the significance of Masonic influence amongst

club directors. Studies concerned with Glasgow football culture have

speculated about the role of Freemasonry in the development of Glasgow

Rangers Football Club. Rangers’ longstanding chairman, and majority

shareholder, Sir John Ure Primrose, established Masonic connections at

Rangers in the late nineteenth century. It has been argued that Freemasonry

acted as a bonding agent at Rangers, ensuring loyalty to the club, and the

loyalty of the club to the Craft.23 The exclusion of Catholics from Masonic

membership – whether by being actively blocked or through the conflict such

membership would have had with their religious belief – meant that this was

another means of excluding Catholics from employment at Rangers. Though the

connection between Liverpool FC and Liverpool Freemasonry was not as

explicitly stated, my own research suggests that anyone at the club with

boardroom ambitions would have found that being a Mason had its advantages

(http://www.freemasonrytoday.com/47/p10.php). At least this seems to have

been the case in the period of the club’s history dominated by its first chairman,

John Houlding. Houlding, who had been a founding member of both Anfield

and Sir Walter Raleigh Lodges, rose through the levels of Freemasonry

attaining the status of Provincial Grand Registrar and Provincial Grand Warden

in West Lancashire during the 1880s. His Masonic career reached its zenith in

1898 when becoming Grand Senior Deacon of England. Houlding was one of

the few Freemasons who attained the “33rd Degree” – the highest possible level

any Freemason can attain, an exclusive order within Freemasonry restricted to

seventy five members at any one point in time.24 Between 1892 and his death in

1902, eight of the thirteen directors and two secretaries at Liverpool FC were

Freemasons.25 At provincial level in West Lancashire and Cheshire, Liverpool

directors made their mark: J.J Ramsey and John McKenna were Provincial

Grand Deacons in West Lancashire, as was club secretary, Simon Jude.

David Kennedy

11

Director, Edwin Berry, attained Provincial Grand Registrar status in West

Lancashire, whilst his brother, and fellow director, Albert E. Berry, achieved the

rank of Provincial Grand Deacon (Cheshire). In the period after Houlding’s

death to the First World War, this pattern of Masonic association was

maintained at Liverpool FC. Of the nine new directors joining the Liverpool

board after 1902, four directors: William C. Briggs, Richard L. Martindale,

William R. Williams and Albert Worgan,26 were Freemasons. Briggs and

Martindale both reached the status of Provincial Grand Deacon through their

respective lodges, Anfield Lodge and Toxteth Lodge, thereby maintaining an

earlier Liverpool director tradition of achieving prominence within local

Masonic circles. A letter to a Freemasonry journal underlines the pride felt by

Masons in Liverpool for the part the Craft has played in the club’s history.

http://www.freemasonrytoday.com/50/p19.php Is it reasonable to suggest,

then, given the extensive Masonic connections established at Liverpool FC, that

this – along with the Unionist politics of many senior members of the club –

would have contributed to the establishment of a common religious ethos at the

helm of Liverpool in its formative period similar to that established at Glasgow

Rangers?

§

If there was a demonstrable difference in terms of attitude to religious and

political affairs between the clubs at boardroom level – and this does appear to

have been the case in an earlier period – did this necessarily translate into the

clubs operating along sectarian lines? I think, overall, the answer to this question

is that they did not, although the matter is a complex one. Certainly, the scope

was there for the two clubs to capitalise and prosper on a sectarian business

model. In a number of Scottish and Northern Irish towns religious and political

leaders took the crucial lead in the development of professional football

organisations. They viewed ethnic Irish football clubs as a form of cultural capital

able to consolidate religious and ethnic identity in the face of a hostile Protestant

Unionism. In Liverpool, however, a city similarly riven with sectarian tensions,

this lead was not forthcoming.27 Though some in the Liverpool Irish community

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

12

attempted to form their own football organisations (Liverpool 5th Irish being

probably the most obvious example28) this avenue of setting up specifically

ethno-religious football clubs was not pursued by the city’s Irish Catholic

hierarchy. Under these circumstances the established professional football clubs

of Liverpool stood to profit by judicious appeals to different religious

communities – to indulge in the type of carving up of the local football market

associated, for example, with the ‘Old Firm’ clubs of Glasgow.

One of the means a symbolic message could have been sent out by the clubs

would have been to follow a recruitment policy that encouraged the signing of

players from a particular background (or, putting it another way, a policy of

excluding players from a particular background) as was the case with Glasgow

Rangers or Belfast club, Linfield. An unwritten ‘policy’ of not signing Roman

Catholic players was in place at those clubs until well into the latter decades of

the twentieth century, and it became a crucial strategy in securing a sectarian

division in local demand for football as supporters identified with the playing staff

assembled before them. In the case of Glasgow Rangers this went as far as the

marginalisation of players within the club who had married Roman Catholics.

Ironically, an argument often used by those defending the Merseyside clubs from

the charge of sectarianism has been to highlight Everton’s signing of Irish born

players, especially in the 1940s and 1950s, as an explanation for the ‘confusion’

over religious links attributed to the two Liverpool teams. In the mid twentieth

century Everton forged connections with clubs in Ireland, such as Dundalk and

with Dublin teams Shamrock Rovers and Shelbourne. These links reaped a

harvest of players, such as Tommy Clinton, Peter Corr, Tommy Eglington, Peter

Farrell, Jimmy O’Neill, George Cummins, Dan Donovan, Mick Meagan and Jimmy

Sutherland. The employment of former Manchester United captain and Irish

international, John Carey, as manager in 1958 gave the team a distinctive

“Hibernian” flavour - a point made by former Everton player Brian Harris in his

biography, and in a not entirely complimentary fashion.29 However, well before

the post Second World War era Everton had established a frequent supply line in

Irish talent, a connection so rich as to be described as an Eireann tradition. The

David Kennedy

13

first signing from Ireland was Jack Kirwan, a player plucked from Gaelic Football

outfit St James Gaels in 1898. Kirwan’s move to Goodison was followed by

Shelbourne team mates Valentine Harris (another convert from Gaelic Football)

and Billy Lacey – men who went on to manage the Irish Free State national team in

the 1930s). Other notable Irish internationals that went on to play for Everton

were Billy Scott, Belfast Celtic’s Jackie Coulter and Alex Stevenson.30 Probably

for this reason Everton were the first English club to have a supporters’

association set up in Ireland, becoming the first example of a club with a large

‘overseas’ support, as hundreds of Irishmen travelled to Liverpool for Everton

games. Symbolically, the connection between Everton and Ireland was cemented

with the move of Everton’s greatest ever player and iconic figure, William Ralph

(Dixie) Dean, to Sligo Rovers in 1939; Dean going on to win the Irish Cup with

Rovers in the 1939/40 season.

By contrast, Ireland was a virtually untapped market for Liverpool FC until the

end of the twentieth century. During the 1980s Liverpool signed a host of Irish

international stars including Ronnie Whelan, Steve Staunton, Jim Beglin and

Michael Robinson. This relatively late influx into the club has led some to talk of a

less welcoming attitude toward Irish born players at Liverpool FC than

traditionally was extended by their near neighbours. However, the reason for this

disparity can perhaps partly be explained by the initial scouting networks set up

by Liverpool. Through the club’s first secretary-manager, John McKenna,

Liverpool from their inception targeted (and out of a necessity as a newly formed

club to ‘hit the ground running’), proven players of quality from Scotland, a

traditional route followed by many English clubs seeking professional players

during this period. McKenna immediately signed thirteen Scots professionals

from which were constructed the celebrated ‘team of macs’ of 1892. This was a

deep well of talent that McKenna returned to in his four years as club secretarymanager

between 1892 and 1896, and it became a scouting pattern which his

successors kept faith with over the years. Thus, a tradition was set in place. In the

words of one Liverpool fan:

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

14

Liverpool FC has been blessed with the impressive contributions of many

nationalities down the years, but the impact of Scottish players and

managerial staff is arguably unequalled at Anfield…Liverpool’s history is

built on the shoulders of Scottish players and their grit, skill,

determination and excellent leadership and motivational ability. 31

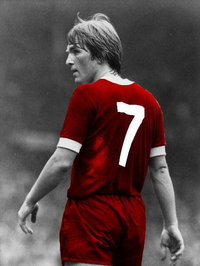

In total the club has signed a staggering 149 Scots-born players since 1892 that

went on to play first team football. They include the names of the most celebrated

players in the club’s history: Alex Raisbeck, Ted Doig, Billy Liddell, Ian St.John,

Ron Yeats, Kenny Dalglish and Graeme Souness. It has been argued that this

heavy bias toward recruitment north of the border inculcated the club with ‘a

robust Scottish Protestant ethic’.32 The fact that this Scottish recruitment included

players from both sides of the religious divide, though, questions the validity of

stressing the sectarian importance of the sourcing of players from Presbyterian

Scotland rather than Catholic Ireland. The earliest Liverpool teams included many

players transferred from Scots-Irish clubs who were of Irish Catholic descent,

such as Andy McGuigan from Hibernian, and James McBride and Joseph McQue

from Celtic. The celebrated Manchester United manager, Matt Busby, signed in

1935 and made club captain soon after, was a devout Roman Catholic.

Similarly, the claims suggesting that the Merseyside clubs operated an informal

city based scouting arrangement along religious lines must also be rejected.

Specifically, this was said to have worked on the basis of Everton and Liverpool

casting their net over promising young players within the city’s schoolboy

representative teams: Everton being given the opportunity of choosing the cream

of local Catholic talent; Liverpool allowed free rein to do the same with state

schooled or Protestant schooled boys. However, and certainly in the post-Second

World war period, it is clear that many players brought up in the Liverpool-Irish

community had little problem in becoming Liverpool players. In the 1950s and

1960s boys from Catholic backgrounds such as Bobby Campbell, Jimmy Melia,

Chris Lawler, Tommy Smith and Gerry Byrne were signed by Liverpool. In fact,

Byrne was signed up for Liverpool whilst playing for the Liverpool Catholic

Schoolboys team.33

David Kennedy

15

§

Beyond signing policy, another way that the Merseyside clubs could have

stressed differing identities would have been by forging exclusive associations

with particular religious or ethnic organisations. Did differences here provide

substance for the Catholic-Protestant religious tags that have been attached to

each football organisation? Again, we can go back to the example of Scottish

football where the use of such symbolism was employed to secure and reinforce

support from ethno-religious communities. Glasgow Rangers’ association with the

Orange Order, for instance, underlined their Protestant and Unionist credentials.

On occasion, the Glasgow club offered its Ibrox stadium as a venue for the annual

religious service held by the city’s Orange Lodges, and allowed its team to play

benefit matches in Northern Ireland for a variety of Orange Order charities. For

their part, Rangers rivals, Celtic, emphasised their role as a totem of Irish

Catholic cultural identity in the city by, for example, making its founding

principle the provision of charity for the Catholic poor and by making their

ground Celtic Park available for the holding of Roman Catholic mass on important

feast days during the religious calendar.34

This state of affairs was not repeated on Merseyside. All available evidence

points toward a non-partisan approach to community relations by the clubs, with

neither Everton or Liverpool predominantly favouring one particular religious

denomination over another. For example, the Liverpool Catholic schools annual

sports days were hosted alternately at Goodison Park and Anfield in the Inter

War period. Another institution enjoying the patronage of both clubs was The

League of Welldoers: a charity set up in the Victorian period at Limekiln Lane, off

Scotland Road in the heart of “Irish Liverpool”. Also known as “Lee Jones’” after

its philanthropist founder, the charity provided a crucial intervention in the pre

welfare state era amongst the poor and destitute of the Scotland Road area.

Everton hosted food parties and organized games for children sent by the

charity, whilst Liverpool director Richard L. Martindale was one of the League’s

governors. Everton and Liverpool football clubs also appear to have been on

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

16

friendly terms with the premier Catholic college in Liverpool: St Francis Xavier.

My research also reveals that both clubs gave assistance to St Francis Xavier’s by

providing coaches to help train their various sporting teams.

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp....91~tab=

citations Everton player – and future club director - Daniel Kirkwood, and

Liverpool player, Alex McCowie, were seconded to Saint Francis Xavier as

coaches.35 And the outreach efforts of the clubs were not restricted to the

Catholic community. In the pre Second World War period the players and

management of Everton and Liverpool took part jointly in services held by

Nonconformist congregations. These so-called ‘Football Sundays’ were formal

affairs, often with a civic dignitary in attendance, with directors and players from

each club called upon to speak.

More typical of Everton and Liverpool’s community support, however, was their

aiding of secular causes, such as alms giving to local hospitals. Stanley Hospital in

the Kirkdale district of Liverpool in particular was the frequent recipient of

financial donations from both clubs. They also appear to have taken an interest in

alleviating the hardship of the local labour force in periods of economic

downturn. In 1895, at the height of a bleak winter of trade inactivity in the port,

Everton donated £1000 to relief agencies and set up a soup kitchen to provide for

12,000 people. And in 1905 both clubs agreed to donate a third of the gate

receipts from the Liverpool Senior Cup final to the city’s Unemployed Fund

(although the extent of the Liverpool board’s good will in this respect is

questioned by their later refusal to allow matchday collections for striking

Liverpool dockworkers).36

§

Returning to our question, then, Is there any substance to the assertion that

religious differences in some way have played a part in the history of the

Merseyside clubs? Perhaps a judicious conclusion to make would be that, though

David Kennedy

17

there is no compelling argument to make the case that football on Merseyside

followed the path taken in Glasgow or Belfast, there was, in some respects, a

significant cleavage between the clubs that does warrant acknowledgement.

Certainly, the patterns of control at each club in the late Victorian and Edwardian

period are startling in their difference, and the political distinctions between

them would not look out of place when comparing the hierarchy of Glasgow’s Old

Firm or that of, say, Belfast Celtic and Linfield. Historians plotting the

development of football clubs associated with religious sectarianism in Scotland

and Northern Ireland, for example, are firm in their opinion that the identities of

these clubs are less a result of their being initially founded as sporting

outgrowths of churches or chapels than they are the product of long established

boardroom hierarchies who stamped them in their own image.37 Clubs like

Glasgow Celtic, Hibernian and Belfast Celtic, founded to provide charity to the

Catholic poor and as an outreach to young Catholic men, soon found their

direction dictated by a local business elite, many of whom were involved in

Nationalist politics. Similarly, the identity of Glasgow Rangers and Linfield – clubs

which, if not being founded by Presbyterian chapels certainly had their roots

within that religious tradition38 – were moulded by the Unionist politics of men

dominating their boardrooms. For this reason alone, the claims of a religious

schism in Merseyside football circles cannot simply be dismissed as the product

of a tendency amongst some supporters to look for convenient binary opposites.

In terms of determining whether such obvious differences in leadership impacted

on the running of the club, it could, one supposes, be argued that it may have led

to differences in the targeting of imported players, and that Everton’s forging

strong links with Ireland was a “follow on” of some aspect of its boardroom

profile. Such a policy might explain the large amount of anecdotal evidence

professing Everton to be a team supported by Liverpool Catholics: the amount of

Irish players the club attracted to it igniting a certain degree of ethnic pride in

Everton amongst the city’s Irish-born or those of Irish descent. One writer with

knowledge of both the Glasgow and Merseyside professional football scene

believed this to have been the case. ‘Everton Football Club, like Celtic Football

Club’, wrote Celtic historian, James Handley, ‘owed its success to immigrant

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

18

support, the Irish in Liverpool rallying wholeheartedly round it’. This is an

opinion still at large today amongst onlookers to Merseyside football’s affairs. 39

However, despite there being a marked difference between Everton and

Liverpool in the volume of players selected from Ireland, evidence suggests that,

overall, there was no attempt by the clubs to operate discriminatory policies on

the grounds of religious sectarianism when employing playing staff. And neither

does there appear to have been any policy to build up support amongst one

section of the population to the detriment of attracting support from another

section. There was, in short, no obvious effort to secure a support base by

repeating the type of divisive practices via “community outreach” found in

certain other football cultures elsewhere in Britain (nor, indeed, to mirror the

divisions found in the city of Liverpool on every level: from schooling to housing;

from welfare provision to workplace recruitment). This latter point may have

prompted the Liverpool Lord Mayor’s observation in 1933 that the two clubs had

done more ‘to cement good fellowship…than anything said or done in the last 25

years’ - a period blighted by sectarian unrest in the city.40

Notes

1 John Williams Into the Red: Liverpool FC and the Changing Face of English Football, p.10.

2 John Woods Growin’ Up: One Scouser’s Social History of Liverpool, p.43.

3 Liverpool Echo 17th December 2002. ‘Cilla and Ricky’s “Scouseness” Test’.

4 Tommy Smith and Dave Stuckey I Did It the Hard Way, p.14.

5 See: P.Ayres, Life and Work in Athol Street, (Liverpool, p69; T.Campbell, Rhapsody in

Green: Great Celtic Moments, pp.285-286; B.Clegg, The Man Who Made Littlewoods, p183;

Alan Edge, Faith of Our Fathers, pp.96-99; J.E.Handley, The Celtic Story: A History of the

Celtic Football Club, p27; D.Hill, Out of His Skin: The John Barnes Story, pp.68-69; B.Murray,

The Old Firm: Sectarianism, Sport and Society in Scotland, p96n; M. Owen, Everton in

Europe: Der Ball ist Rund, 1962-2005, p. 178-79; S. Redhead, Football with Attitude, p.20;

T.Smith, I Did it the Hard Way pp.14-15; J.Williams et al, Football and Football Hooliganism

in Liverpool, p18.

6 Ian Colvin, quoted in Dan Jackson, ‘Friends of the Union’, Liverpool, Ulster, and Home

Rule, 1910-1914’, Transactions of the Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, number

152, 2003, p.114.

7 Davies, Liverpool Labour: Social and Political Influences on the Development of the Labour

party in Liverpool, 1900-1939, p.19

David Kennedy

19

8 Liverpool Daly Post (Hereafter LDP) 29th October 1892.

9 For Clayton see: Southport Liberal Association, Annual Reports, 1899-1930; Executive

Committee Meeting Minutes, 1880-1930. For Baxter see: Liverpool City Council Annual

Committee and Sub-Committee Reports, 1906-1921; Baxter’s funeral report, Liverpool

Mercury, 28 January 1928. For Mahon see: See Bootle Times, 11 January and 1 March 1889

for reports of Walton Liberal Association meetings. There are no surviving records of the

Liverpool Liberal Party. Confirmation of Dr Whitford’s status comes from local newspaper

coverage of Liberal Party meetings during the period under review (see, for example,

LDP, 13 April and 10 and 11 June 1892). For Cuff see: press reports of local Liberal Party

meetings in the early 1890s. See Bootle Times, 26 April 1890; LDP, 18 October 1892. For

Wade (the brother of J.A.Wade, chairman of the Walton Liberal Association) see LDP, 22nd

and 26th October; 1891, 5th and 11th April 1892; and 18th June. for Alfred Gates see LDP,

23rd May, 1942.

10 Liverpool Constitutional Association, minutes and annual reports, 1860-1947.

11 Liverpool City Council Annual Committee and Sub-Committee Meeting Minutes, 1890-

1910. Other Liverpool FC directors involved in Conservative politics were: Harry Oldfield

Cooper, a member of the Liverpool Junior Conservative Club (see LDP, 20 May 1915), and

Thomas Croft Howarth, a figure key to the formation of the club, the leader of the

Conservative group in the Liverpool Parliamentary Debating Society (see LDP, 13 October

1939.

12 LDP, 11th June 1892. See also Porcupine, 26 December 1896 .

13 For Gates see LDP 21st Oct. 1910; Liverpool Catholic Herald 1st Nov. 1913. For Mahon see

Bootle Times 8th Feb. 1890. (See also Bootle Times, 11th Jan. and 1st March 1890 for more

evidence of Mahon’s presence with the pro Home Rule Walton Liberal Associaition.

14 For Baxter see: ‘Loss to Liverpool Catholicity’, Liverpool Catholic Herald, 4 Feb. 1928, 2;

obituary, LDP, 28 Jan.1928). For details on Wade see LDP, June 18th 1892.

15 Liverpool Courier (hereafter LC), 19th May, 1892.

16 LDP, 29th Oct.1898; Speaking in Porcupine, 22nd October 1904, Berry describes himself

as being ‘zealous to bring Ritualistic offenders to book’.

17 LDP, 17th May 1892.Waller, p.157

18 Waller, Democracy and Sectarianism: p.286.

19 Whittingham Jones, Barbara, The Pedigree of Liverpool Politics: White, Orange and

Green, p.7. Down With the Orange Caucus p.6-7

20 Salvidge of Liverpool, Stanley Salvidge, p.186.

21 For details on John Houlding, Richard H.Webster, William Houlding and Thomas Croft

Howarth see press reports of Working Men’s Conservative Association district meetings

Bootle Times, 4th Dec. 1886, 2 Feb. 1895; LDP, 3 Feb. 1892). For Simon Jude see LDP, 30

January 1897. For Edwin Berry see LDP, 23 Nov. 1925. For B.E. Bailey see Liverpool

Conservative Association minutes and annual reports, 1890/91. For Albert E. Berry see

Liverpool and Merseyside Official Red Book, ‘Political Associations: Working Men’s

Conservative Association’, 1925. For R.K. Milne see LDP 4th May 1953. For details for John

Holland see LDP 30 Jan. 1912. For J.A. Willox see Liverpool and Merseyside Official Red

Book, ‘Political Associations: Working Men’s Conservative Association’ 1902. For E.P.

Walker see LDP, 30th Jan. 1897. For Archibald Salvidge see Waller, Democracy and

Sectarianism p.509.

22 Finn, Gerry P.T., ‘Scottish Myopias and Global Prejudices’, in Finn, G.P.T. and

Giullianotti, R. (eds), Football Culture: Local Contests, Global Visions, pp.60–1.

23 The significance of Freemasonry on Glasgow football culture has been touched upon by

Gerry P.T. Finn, ‘Racism, Religion and Social Prejudice: Irish Catholic Clubs, Soccer and

Scottish Society’, International Journal of the History of Sport, Vol.8, (1), (1991) pp.72-95,

and by Bill Murray, The Old Firm in the New Age: Celtic and Rangers Since the Souness

Revolution, pp.173-77.

24 LC 19 March 1902. Stephen Knight, The Brotherhood, p.41

25 For W.C.Briggs see LC, 23 February 1923; John McKenna, LDP, 23 March 1936;

JJ.Rarnsey, LC, 18 October 1918. For Simon Jude, see LC, 2nd January, 1922. For A.E.Berry

see LDP, 27 February 1931 Edwin Berry, LC, 23 November 1925. Hamer Lodge (1395)

J.C.Brooks; Wilbraham Lodge (1713) A.E.Leyland. Source: Grand Lodge of England

Country Returns

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

20

26 For W.C.Briggs see LC, 22d February, 1923; R.L.Martindale see LC, 24th February, 1926;

W.R.Williams see LDP&M, 22nd January, 1929; A.Worgan see LC, 16th October, 1920.

27 By contrast to Scotland, at the end of the nineteenth century, second and third

generation (that is to say the Liverpool-born) Irish, were increasingly focused on the

struggle for the rights of citizenship (manifest in their commitment to municipal politics) as

much as they were for the rights of Home Rule for Ireland; a denationalisation process

encouraged by the Catholic Church in the city anxious that Catholicism was not so

synonymous with Irish-Catholicism that it would adversely affect its capacity to cut across

Irish-British identities in accordance with its main aim of integration. (See Hickman, Mary

J. Religion, Class and Identity: The State, the Catholic Church and the Education of the Irish

in Britain.

28 The team’s origins lay in the 5th Irish Volunteer Rifle Brigade, a body of men recruited

exclusively from the Liverpool Irish Catholic community. ‘The Irishmen’ as they became

known were formed in 1888 in the Everton district and played their football competitively

in the Liverpool and District Amateur League and West Lancashire and District League.

The team were disbanded in 1894.

26 ‘I don’t have fond memories of Johnny Carey’, wrote Harris of his first Everton manager,

‘he favoured the Irish contingent at the club and the two of us did not get on at all’. Quoted

in Westcott, C., Brian Harris: The Authorised Biography’ , p.37.

29 ‘I don’t have fond memories of Johnny Carey’, wrote Harris of his first Everton manager,

‘he favoured the Irish contingent at the club and the two of us did not get on at all’. Quoted

in Westcott, C., Brian Harris: The Authorised Biography’ , p.37.

30 See Young, Percy Football on Merseyside

31 http://www.liverpool-kop.com/2008....de.html

32 Figures on Liverpool’s Scottish players from Liverpool FC historian Eric Doig. Eric

calculates this to be 23 per cent of all playing staff at the club since its inception. Quotation

regarding Liverpool’s ‘robust Scottish Protestantism’ taken from: Hill, David Out of His

Skin: The John Barnes Story, p.69.

33 Williams, John (Ed), Passing Rhythms: Liverpool FC and the Transformation of Football,

p.20); http://www.lfchistory.net/redcorner_articles_view.asp?article_id=2213

34 Murray, Bill The Old Firm in the New Age: Celtic and Rangers Since the Souness

Revolution; Murray, Bill The Old Firm: Sectarianism, Sport and Society in Scotland.

35 See The Xaverian, January, 1899, 202-03; November, 1899, p.366. T. Mason, The Blues

and the Reds: A History of the Everton and Liverpool Football Clubs, p18.

36 Percy Young, Football on Merseyside p.56; Belchem, John, Irish, Catholic and Scouse,

p.242.

37 Finn, Gerry P.T. ‘Racism, Religion and Social Prejudice: Irish Catholic Clubs, Soccer

and Scottish Society – II Social Identities and Conspiracy Theories’, International Journal of

the History of Sport vol.8, number 3 (1991) pp.370-397. Burdsey D. and Chappell R. ‘“And

if You Know Your History…” The Sports Historian, number 21 (1), (2000) pp.94-106

38 Rangers were formed in 1873 out of the remnants of a Presbyterian boys football club.

39 Handley, James E. The Celtic Story: A History of the Celtic Football Club. . Irish social and

economic commentator, David McWilliams, underscores the point made by Handley in his 2007 article

on the fate of what he terms ‘HiBrits’ (the offspring of Irish emigrants to Britain: the Hibernian-

Britons). On Merseyside football, and Wayne Rooney’s rise to prominence in particular, McWilliams

writes that ‘Father Inch [parish priest of the Blood of the Martyrs Catholic Church, Croxteth] is a

Toffee true and true. Everton Football Club is the Irish team in Liverpool and it’s no surprise therefore,

that Rooney is a Blue.’ http://www.davidmcwilliams.ie/2007....dsgain#

comments

40 Lord Mayor Cross Liverpool Echo, 5th Jan 1932.

David Kennedy

21

Bibliography

Ayres, Pat Life and Work in Athol Street (Liver Press, 1997)

Belchem, John, Irish, Catholic and Scouse (Liverpool University Press, 2007)

Campbell, Tom Rhapsody in Green: Great Celtic Moments

(Mainstream,1990)

Clegg, Barbara The Man Who Made Littlewoods (Hodder &

Stoughton,1993)

Davies, Sam Liverpool Labour: Social and Political Influences on the

Development of the Labour party in Liverpool, 1900-1939 (Keele, 1996)

Edge, Alan Faith of Our Fathers (Mainstream, 1997)

Finn, Gerry P.T. and Guilianotti, R. (eds) Football Culture: Local Conflicts,

Global Visions (Routledge, 2000)

Handley, James E. The Celtic Story: A History of the Celtic Football Club

(Stanley Paul,1960)

Hickman, Mary J. Religion, Class and Identity: The State, the Catholic

Church and the Education of the Irish in Britain. (Avebury, 1995)

Hill, David Out of His Skin: The John Barnes Story (WSC Books Limited,1989)

Murray, Bill The Old Firm in the New Age: Celtic and Rangers Since the

Souness Revolution (Mainstream, 1998)

Knight, Steven The Brotherhood: The Secret World of Freemasonry

(HarperCollins1983)

Mason, Tony The Blues and the Reds: A History of the Everton and Liverpool

Football Clubs (1985)

Murray, Bill The Old Firm in the New Age: Celtic and Rangers Since the

Souness Revolution (Mainstream, 1998)

Murray, Bill The Old Firm: Sectarianism, Sport and Society in Scotland

(revised edition. Mainstream, 2000)

Owen, Mike Everton in Europe: Der Ball ist Rund, 1962-2005 (Countyvise,

2005)

Redhead, Steven Football with Attitude (Ashgate, 1991)

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

22

Salvidge S. Salvidge of Liverpool, (Hodder & Stoughton, 1934)

Smith T and Stuckey D I Did It the Hard Way (Arthur Baker, 1980)

Waller, Phillip J. Democracy and Sectarianism: A Political and Social History

of Liverpool, 1868-1939 ((Liverpool University Press,1981)

Westcott, C., Brian Harris: The Authorised Biography’ (NPI Media Group,

2003)

Whittingham-Jones, Barbara Down With the Orange Caucus (Liverpool,

1936)

Whittingham-Jones B. The Pedigree of Liverpool Politics. White, Orange

and Green (Liverpool, 1936)

Williams, John Football and Football Hooliganism in Liverpool (Leicester

University, 1987)

Williams, John (Ed), Passing Rhythms: Liverpool FC and the Transformation

of Football (Berg, 2001)

Williams J. Into the Red: Liverpool FC and the Changing Face of English

Football (Mainstream 2002)

Woods Growin’ Up: One Scouser’s Social History of Liverpool, (Palatine,

2007)

Young P.M. Football on Merseyside (Stanley Paul, 1963)

1

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

By David Kennedy

People ‘dressed’ their houses to advertise Cup Final footballing

allegiances, though my Mum would never allow my brother’s Evertonian

blue to go up in case neighbours or passers-by mistakenly took us for

Catholics – John Williams (football sociologist)1

It was strange in the 1930s for a Catholic to support Liverpool – John

Woods (Liverpool author).2

In Liverpool, even in the two-ups and two-downs, most Protestants were

Conservative and most Catholics were Labour, just as Everton was the

Catholic team and Liverpool the Proddy-Dog one – Cilla Black (singer)3

Being a Roman Catholic school, religion played a large part in our school

life. Pop Moran even tried to turn me off football at Anfield – Catholics

were traditionally Everton supporters and players, Liverpool were the

Protestant team. Pop honestly thought that being a Catholic I wouldn’t be

happy at Anfield – Tommy Smith (ex Liverpool FC player and captain)4

A sectarian division between Everton and Liverpool football clubs is, for some, an

irrefutable part of local football culture. There is a prodigious amount of

anecdotal evidence claiming Everton to be the team traditionally supported by

the city’s Catholic population and Liverpool being predominantly supported by

Protestants. For others, however, sectarian affiliation is more urban myth than

reality: a tribal impulse amongst some fans to shore up and sharpen their

identity by suggesting a deeper meaning to support for the two clubs.5 Orthodox

opinion lies with the latter viewpoint, and football historians in particular have

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

2

dismissed notions of sectarianism as being without foundation and a divisive

intrusion into the study of both clubs. The issue, though, has never been

investigated in any great depth and, perhaps, deserves closer scrutiny than the

cursory attention afforded it. Whilst the claim of religious differences has little or

no meaning in defining the relationship of the modern day Everton and Liverpool

football clubs, the specific question to address is whether there is any justification

for the perception that, in an earlier period, the basis for such claims existed?

§

Naturally, claims of past sectarian connections have been resisted strongly by the

clubs themselves. Official club literature goes to some lengths to deny this

possibility by stressing Everton and Liverpool’s shared origins in order to

downplay what they view as nonsensical claims of sectarian affiliation. However,

it would be a mistake to dismiss perceptions that each club has acted as standardbearer

for distinct communities simply because of their shared point of origin.

The split of Everton FC in 1892 that brought Liverpool FC into existence saw the

emergence onto the football scene of a body of men with strong political

identities. The men who controlled the fortunes of Everton and Liverpool football

clubs also took an active part in local politics and it would be strange, given the

political environment these men operated within, that football in the City of

Liverpool could have remained untouched from matters of religious controversy

and discretely contained in a purely sporting context. To understand why this

would be so it is necessary to take a short detour into the sectarian history of

Liverpool politics.

During the pioneering period of professional football in Liverpool, religious

sectarianism dominated local life – affecting housing, schooling, and the city’s

occupational structure. By the mid-nineteenth century almost a quarter of the

city’s population were Irish born, and by the century’s end Liverpool remained a

key destination point for an exodus of Irish Protestants and Catholics. Friction

between the city’s Protestant and Catholic populations was a feature of the social

landscape – on many occasions erupting into street violence and rioting between

David Kennedy

3

ethnically divided communities. Some historians have argued that the ferocity of

the hostility between Irish Catholics in Liverpool and the “native” British and Irish

Protestant community surpassed the sectarian divide in Scotland, and only stands

close comparison with the experience of towns of Northern Ireland: ‘Liverpool –

sister of Belfast, rough, big hearted, Protestant and Unionist’.6 Like no other

mainland British city, Liverpool reflected the contours of the ongoing struggle in

nineteenth century and early twentieth century Ireland between Unionism and

Nationalism over the matter of Home Rule for Ireland.

Liverpool, therefore, was a harsh environment for the class-based politics found

elsewhere in England to prosper in. The local Labour Party struggled to gain a

commanding foothold in the city until well into the twentieth century. ‘Liverpool’,

the frustrated Labour leader, Ramsey MacDonald, wrote in 1910, ‘is rotten and we

better recognise it’.7 The local Home Rule supporting Liberal Party and, more

especially, the Conservative-Unionist Party were more adept at competing for

civic power by recourse to ethno-religious politics. The Liberals used their

commitment to Irish Home Rule to appeal directly to many Irish voters. By forging

an alliance with the local Irish party, the Liberal agenda tended to be

synonymous in most people’s eyes with defending the rights of Catholic voters in

the city. Their political rivals predictably put the matter more bluntly. Tory

leader William.B. Forwood offered the stark choice to the municipal electorate of

being either:

…well governed by the Conservative Party as it had for the past 50 years,

or governed by Home Rulers who had no interest whatever in Liverpool

but were simply in the city council to further the political interests of

Home Rule in Ireland. It was not a question of handing over the control of

the council to Messrs Holt, Bowring and Rathbone [Liberal Party

grandees] but to Messrs Lynskey, Taggart and Kelly [Irish Nationalist

councilors].8

Liberal organisation, though, was weak in Liverpool compared to the

Conservatives, who rather more successfully courted the native working class

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

4

electorate by being “sound on the Protestant ticket”. As the party viewed by

many as the political representation of the ties between Church and state, the

Tories enjoyed a fruitful relationship with the Protestant majority amongst the

electorate. Liverpool’s Tory Party hierarchy had traditionally played on the

emotions of the Protestant working class of the city by appealing beyond their

class interests to their religious identity. A brand of popular Toryism, therefore,

carried the day in Liverpool: deference shown to the Tory elite by the Protestant

working class (and their support at the ballot box) was rewarded by the party’s

close identification with the values and institutions they held in esteem, and

opposition to any significant improvement in the condition of the Irish Catholic

working class – more especially in the fiercely competitive casual labour market.

By playing the Orange card in this way the Tories (for all but a handful of years in

the 1890s) retained municipal control of Liverpool until the 1950s.

The important point to make here is that, whereas in other towns the issues

primarily to be addressed and contested by local parties would be the more

prosaic matters of, say, housing and health provision, or the setting of rates, in

Liverpool “Imperial affairs” (that is, the stance taken by ward candidates on

religion and the Irish Question), were paramount. For this reason it would be

completely understandable, given the high incidence of football club directors

active in the local Liberal and Conservative parties, if ethno-religious labels

became attached to Everton and Liverpool football clubs via the politic views

held by those directors.

I have highlighted elsewhere the strongly partisan political dimension to the

Everton split in 1892: http://www.evertoncollection.org.uk/article?id=ART74553

In the wake of that event the Everton boardroom became a relative stronghold of

men involved in Liberal politics, whereas the Liverpool boardroom was an almost

exclusive preserve of men involved in some way with the local Conservative

Party. In the Everton boardroom, James Clement Baxter was Liberal city

councillor for Liverpool’s St.Anne’s ward; George Mahon – Everton’s first

David Kennedy

5

chairman – was committee member of Walton Liberal Association; Dr William

Whitford was chairman of Everton and Kirkdale Liberal Association; William.R.

Clayton was the chairman of Formby Liberal Association; Alfred Gates was

leader of the Liberal Party in Liverpool City Council. Two other Everton directors,

Will Cuff and Alfred Wade, were also involved in local Liberal politics.9 All seven

men would become chairmen of the club. By contrast, at Liverpool FC boardroom

involvement in local party politics was of a distinctly Conservative nature. Six

directors: Benjamin E.Bailey, Edwin Berry, John Houlding, William Houlding,

Simon Jude, and John McKenna were members of the Constitutional Association,

the ruling body of Liverpool Conservatism.10 The Constitutional Association

exercised complete control over district Conservative Associations in Liverpool

and affiliated societies and organizations such as the Orange Order. In the

council chamber John Houlding, Edwin Berry, William Houlding (John Houlding’s

son, and fellow director) and club secretary, Simon Jude, were Conservative

councilors representing neighbouring north Liverpool wards. Other Liverpool FC

directors involved in Conservative politics were: Harry Oldfield Cooper, a

member of the Liverpool Junior Conservative Club, and Thomas Croft Howarth,

the leader of the Conservative group in the Liverpool Parliamentary Debating

Society.11

It seems hard to believe that such stark difference in political complexion – and

the connotations they held – would escape the attention of a general population

keenly tuned-in to the attitudes of those involved in public life on matters of

religion. In fact, there were many public statements made by prominent club

members concerning the issues of religion, ethnicity and the all-pervasive matter

of Irish Home Rule to drive the differences home. For example, Everton director,

William Whitford, described as ‘an ardent Home-Ruler’, made an impassioned

speech during the municipal election campaign of 1892 against the blocking of

Home Rule by Ulster Unionists:

Ulstermen do not desire to govern Ireland according to the wishes of the

people of Ireland, but according to the narrow prejudices of the so-called

“loyal minority”. Irish Catholic bishops and priests had not the illegitimate

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

6

power we in this country are asked to believe. Their views are, however,

in accordance with the nationalist aspirations of the Irish people. The

priests had been loyal to the people, unlike the priests of other

denominations…The Irish priests could not and had not the power to lead

the Irish people in temporal matters against their honest convictions 12

Everton director and fellow Liberal-Nationalist, Alderman Alfred Gates (a name

which was ‘as a red rag to a furious bull’ to the Conservative-Unionist Party) was a

‘strenuous advocate of Home Rule’ keen to show that ‘the Orange Tory Party were

losing ground in Liverpool’. Another director of the club and Everton’s first

chairman, Dublin educated George Mahon, helped reorganise the Walton

Liberal Association in the wake of the defection of Liberal Unionists opposed to

Gladstone’s proposed solution to the Irish Question. Mahon was a prime mover in

the Walton Liberal Party’s adoption of the policy plank of Home Rule and was one

of the officers of that district body affirming in the local press their 'total support

for Home Rule'.13 And frequent press reports of directors James Clement Baxter

and Alfred Wade attending Irish Nationalist League meetings would have

underlined for the public a sense of the general sectarian tone of the men

inhabiting the Everton boardroom.14

From figures amongst the Liverpool FC hierarchy, on the other hand, there was

an equally strident and public outpouring of feeling toward the Protestant-

Unionist cause. Founder and Chairman of Liverpool FC, John Houlding, quite

obviously found it difficult to contain his religious leanings as a Conservative-

Unionist and Orangeman whilst carrying out his duties as a Guardian at the West

Derby Poor Law Union. As reported by the Liverpool Courier, as Guardian of the

West Derby Union Houlding pointedly refused granting to Catholic priests any

payment for ministering to Catholic inmates of workhouses whilst allowing such

payment to Church of England and Nonconformist ministers. In reply to a motion

put before the Poor Law Union to make the payment to Catholic priests ‘as an act

of justice and common fairness’ Houlding replied:

I defy any member of the Board or any judge in the land to show him an

Act of Parliament which expressly stated that they should pay Roman

David Kennedy

7

Catholics for services performed in workhouses. If English Unions did

appoint a Roman Catholic priest it is only done by a clear evasion of the

law, and often perhaps for the sake of quietness 15

Another Liverpool FC director, and a successor to Houlding as chairman, Edwin

Berry, leaves us evidence of his vigilance against the re-emergence of an

influential Roman Catholic Church in British society – a matter of much debate in

Liverpool political circles in the late Victorian period. Addressing an audience of

the British Protestant Union in 1898, Berry offered his support to ‘the repression of

lawlessness and Romanising influence’, declaring himself to be a ‘loyal

Churchman with every desire to further the principles of the Church of England

in accordance with the Reformation’. This was a position on the issue he

reiterated six years later when attempting to outflank the challenge of an

independent Orange Order candidate for his council seat.16

A close associate of both Houlding and Berry both in local political circles and at

Liverpool FC was MP for Everton and President of the National Protestant Union,

Sir James A Willox. Willox, the proprietor of the Liverpool Courier, was not a club

director but was an influential large shareholder in Liverpool FC, using a “proxy”

on the board to advance his interests in the club. Willox publicly backed the

decision to set up Liverpool FC out of the remnants of the staff left behind at

Anfield in the wake of the 1892 split and remained a close ally of the club’s board

until his death in 1905. A firebrand in the defence of British dominion over

Ireland, Willox, speaking to a meeting in his Parliamentary Division, attacked

Liberal policy on Ireland: ‘To conciliate four million people in Ireland’ he asked

his audience, ‘are we going to sacrifice one million and a half of loyal Protestants

and faithful lieges of the Queen?’. Speaking to another Conservative audience,

Willox called for ‘more of Cromwell’s courage and more of his religion’ in public

life. 17

The Unionist sentiments of the hierarchy of Liverpool FC are firmly underlined by

the connections many of their directors had with the Liverpool Working Men’s

Conservative Association (WMCA), an organisation affiliated to the Liverpool

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

8

Tory Party machine. The overlap of personnel between the Liverpool boardroom

and the WMCA gives us further scope in understanding how perceptions of a

sectarian football division between Everton and Liverpool could have taken root.

Described as ‘the engine of Protestant power’18 within Liverpool Conservatism,

the WMCA were at the vanguard of anti-Catholic politics in the city. To gain an

appreciation of the nature of this organization we can turn to the words of Barbara

Whittingham-Jones, a local political journalist writing at the height of the WMCA’s

power in the Inter War period. The WMCA and the Orange Order, declared

Whittingham-Jones, were as ‘identical in political outlook as in personnel’. She

described the proceedings on her visit to one branch meeting in 1936:

Meetings at Conservative clubs cannot proceed until an incantation has

first been declared by all present. The chairman opens the meeting by

requiring members who have been guilty of ‘consorting’ with Catholics to

confess their delinquencies and upon doing so they then receive a

warning. Catholics who have strayed in by chance are requested to leave

the room. Even Questions have to be preceded by the formula: “By my

Protestant faith and Conservative principles…” with hand raised in the

Hitler salute. Such is the democratic character of this sectarian classridden

caucus that no Roman Catholic workingmen can join the

Conservative Party in Liverpool or frequent the Workingmen’s

Conservative Association clubs.19

An organization ‘held together by its tough Orange fibre’, the Liverpool WMCA

was predictably staunch on the Irish Question, offering its support for the

maintenance of the Union with Ireland. The Association’s policy prior to the

partition of Ireland was to oppose the breaking up of the Union and to back the

reprisals carried out by the British auxiliary force, the notoriously brutal Black

and Tans, against Irish Republicans. Writing in 1920, the Liverpool WMCA

Chairman, Sir Archibald Salvidge, saluted Black and Tan operations as the

actions of ‘...those who will not submit meekly to the fiendish destruction of life

and property which Sinn Fein gunmen claim as noble acts of heroism…[but,

rather] give Sinn Feiners a taste of their own medicine’. In the aftermath of the

setting up of the Irish Free State in 1921, the Liverpool organisation’s emphasis

David Kennedy

9

merely switched to the safeguarding of Protestant Ulster and the adoption (no

doubt with one eye on local affairs) of “No Surrender” Unionist politics.20

The amount of people involved in the ownership and control of Liverpool FC in

the period under review who were also key figures in the WMCA is quite

remarkable. These included such club luminaries as John Houlding, Edwin Berry

and Benjamin Bailey – all chairmen of Liverpool at some point prior to the First

World War, and key players in this quasi-religious organisation. But the link was

a longstanding affair at the club, stretching beyond the First World War to the

1950s. Director, Albert Edward Berry, succeeded his brother Edwin as WMCA

solicitor in 1925, holding the position until 1931. This post was then passed on to

yet another Liverpool FC director and Conservative councillor, Ralph Knowles

Milne, a position he held until his death in 1954. The club’s solicitor in the 1940s,

Maxwell Fyffe, also provided a connection between Liverpool and the WMCA.

And at shareholder level too the connection was significant: John Holland, one of

the small number of shareholders involved in the club when it was formed in

1892, and who remained a shareholder until his death in 1914, was one of the

founding members of the Liverpool WMCA in 1867 and was the Association’s

longstanding secretary; the aforementioned Sir James A.Willox, was Vice

President of the WMCA. Conservative councillor, Ephraim P. Walker, a major

shareholder in Liverpool from 1899, was a member of the WMCA’s governing

council. And yet another significant shareholding connection was that of Bents

Brewery. Bents held shares in Liverpool FC at a time when control of the brewery

was in the hands of Archibald Salvidge, Chairman of the WMCA and Edward

J.Chevalier, Vice Chairman of the organisation.21

In the context of deep sectarian tensions in Liverpool society, the strong

connection the Liverpool board had with this avowedly sectarian organization is a

significant one. In this respect it is interesting to note that the Glasgow Working

Mens’ Conservative Association were equally central to the early development of

Glasgow Rangers FC.22 The reputation of the Glasgow club as a bulwark of

Protestant and Unionist ascendancy in the West of Scotland is well established.

Red and Blue and Orange and Green?

10

The undoubted influence of the Liverpool WMCA on Liverpool FC’s development

perhaps demonstrates an unconsidered connection, therefore, between the

Merseyside club and that of the stridently Unionist Rangers.

And it is difficult to ignore another similarity in the boardroom profile of the

Liverpool and Glasgow clubs: the significance of Masonic influence amongst